Enhancing Power BI Apps with Emoji

/Your report page names, and in turn, the Power BI app can be enhanced with the judicious use of emoji. I was surprised to find out that the characters came through in full color, and that can help your users find the important pages faster. This can be especially useful in a large Power BI app with dozens of reports and potentially hundreds of pages.

Adding emoji is relatively straight-forward in Windows 10 and 11. Below are the steps for Windows 11.

Double-click on the report page name in Power BI Desktop and position your cursor at the end (or beginning if you prefer).

Press and hold the Windows key, 🪟 then the period key and the emoji picker comes up.

In the search box, type the name or a description of the emoji you are looking for.

Double-click it to add to the tab.

Press enter to save it.

Windows 10 is slightly different. When you launch the emoji picker, there will be a magnifying glass. 🔎Click that, then type the word you are searching for in the report page tab itself. It doesn’t have its own search box. But once you type “star” for example, when you double-click the star, your typed text will be replaced by the emoji.

Note that once you create the app, you can also add emoji to the report names themselves in the “Content” section of the app creation.

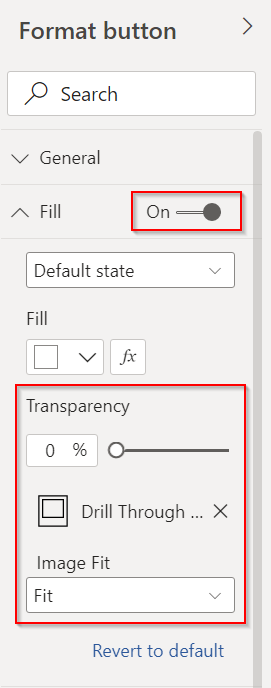

A published app might look like this:

This will help draw users’ attention to the most important pages or reports in the app, but as I said at the beginning, you want to be judicious about this. Less is more here. If every page has an emoji, then it is just clutter and harder to read, and then the emoji to express the look of the app would be 💩.

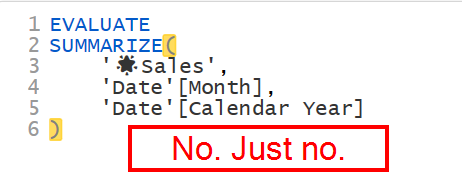

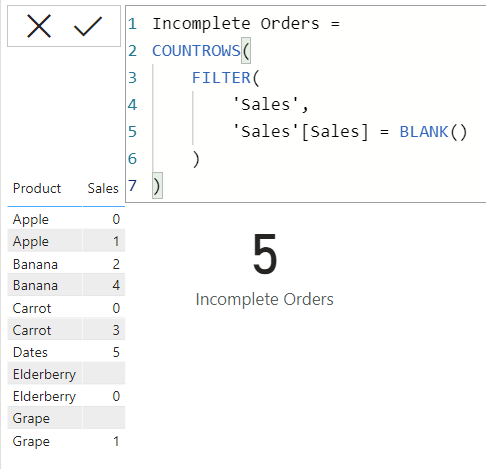

Additionally, do not carry this into the data model itself. I’ve seen people add emoji to table and field names, and that is a train wreck. It makes it harder to use intellisense when typing table/field names, and emoji may not carry their beautiful look through to the DAX editor or M editor, nor through to external tools like Analyze in Excel, DAX Studio, or Tabular Editor. Sometimes the image remains but is just black and white, or worse, you just get a generic ⏹️ icon.

The one exception to this is when I am in Power Query, I will often put an emoji in a step name to remind me to go back and fix that step later. I’d never push that nonsense to production though. 😉

So, spruce up your Power BI Apps, but just a tiny bit!